Update 06/01/2016: You can now download the 6-up and 1-up templates we use in our sketchboarding sessions here.

We’re always on the lookout for new ways of doing things better and faster at Box UK. One area of change that we’re particularly excited about involves our User Experience (UX) design process. Taking inspiration from UX leaders like Brandon Schauer, Leah Buley and Todd Zaki Warfel, we’ve embraced the use of sketchboards.

What are sketchboards?

Sketchboards are a tool to collaboratively generate, evaluate and refine User Interfaces. Based on the Design Studio method, sketchboards are typically created as part of a collaborative approach between user experience designers and other key stakeholders, and helps reduce the time required to achieve the desired results.

An introduction to sketchboards

Like all good User Experience designers, I have a bit of a stationery fetish, with more expensive notebooks and marker pens than could possibly be healthy. I’d always start any interface design on paper before firing up my favourite wireframing or prototyping tools, but my sketches were only ever intended for my eyes only – I’d try a few things out, and as soon as I was happy with my creation, I’d create wireframes of varying fidelity to share with colleagues and clients. Any feedback would be worked back into the wireframes and repeated until everyone was satisfied with the final output. Although fairly time-consuming, this method has been working perfectly well for us and our clients for a number of years.

Back in May of this year, I was fortunate enough to attend UX London, where among many great presentations and workshops, I saw Leah Buley of Adaptive Path present her excellent “Good Design Faster” workshop. The workshop described Adaptive Path’s own process of rapid ideation, communication and collaboration using low-fi sketching techniques and sketchboards. Their process is adapted from the “Design Studio” method, which is a commonplace teaching method in urban and architectural design. Essentially, the Design Studio method is a collaborative sketching workshop, where stakeholders work together to generate, evaluate and refine their designs.

“The goal is to generate a number of concepts, get them out of your head as quickly as possible, and move on.”

– Todd Zaki Warfel

In his book “Prototyping – A Practitioner’s Guide” Todd Zaki Warfel describes sketching as “the generative part of prototyping”. He continues “The goal is to generate a number of concepts, get them out of your head as quickly as possible, and move on.” As firm believers in the power of prototyping, we’ve found that sketching significantly speeds up the prototyping process.

Introducing sketchboarding to Box UK

I first got the chance to put this technique to work on an internal project, so with the reduced risk, I commandeered a colleague, purloined an armful of office supplies from the stationery cupboard and we set to work, sketching and scribbling like men possessed. As we finished a sketch, we discussed and critiqued each other’s work and fine-tuned our sketches before sticking them to the wall. By the end of the day, we’d sketched out an entire application from scratch. Once the sketchboard was complete, we invited colleagues to review our work, letting them know that all feedback and criticism, however negative, was a required part of the process.

For us, the mere fact that we found the sketchboarding technique an enjoyable and productive activity was reason enough for us to include this as an integral part of our design process. It wasn’t long before we were able to try out sketching on a real client. We were delighted to find that the results were even better than our first attempt, and the feedback from our client was way beyond our own lofty expectations.

How do you use sketchboards in UX Design?

We use Jesse James Garrett’s ‘Elements of User Experience’ approach to User Centred Design, so sketchboards fit naturally at the beginning of the Skeleton Plane. As we’ve already covered Strategy (business objectives, users, personas, user needs and success metrics); Scope (functional, content and technical requirements); and Structure (information architecture and interaction design), we already know why we’re building the site, who we’re building it for, what the requirements are and how those requirements are to be structured. We use any relevant information from the preceding stages as inputs – we continually refer to these as we sketch.

Step 1 – Set up your sketchboard

First of all, you need a big, blank canvas on which to stick your inputs and sketches. We bought a huge roll of brown craft paper. Take a length (about 8 to 10 feet usually works for us) and stick it to the wall with lots of BluTack – the sketchboard gets progressively heavier and may fall off the wall if you’re too parsimonious with your sticky stuff.

Step 2 – Inputs

Gather any information that you’ll need to guide you through your sketching, whether it’s sitemaps, flowcharts, scope items, user needs or personas or any inspiration that you think will help, and stick these to the left hand side of your sketchboard. I like to include a list of the interfaces that are required in the session so I know my target at the outset.

Step 3 – Thumbnail sketches

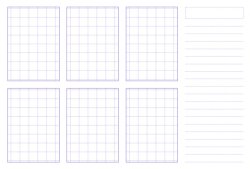

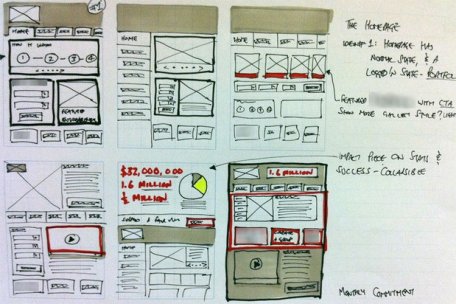

Start with a 6-up template and give yourself a fixed amount of time (say 10 to 15 minutes) to draw as many different versions of the interface you’re going to work on. Try out any idea that springs to mind. Don’t like the vertical navigation? Try horizontal tabs. Too many photos on the home page? Try a carousel.

Use the lined area on the right of the page for text annotations, notes-to-self and anything else that helps to communicate your idea.

Fine detail isn’t important here (as you’ll see from the following photo) – the point is to get your ideas down on paper. Don’t know where to start? – just do something, then change it.

Once you’ve done your thumbnail sketches take a step back and think about which one works best. Maybe you like some parts of one, and parts of another. Do another thumbnail sketch if this is the case, then refine it in the next step.

Step up your user experience game by adapting to modern user needs in the digital age.

Step 4 – Refinement sketch

Now take a 1-up template and start refining your preferred thumbnail sketch. Again, give yourself a fixed amount of time to complete the task, say 10 minutes.

The extra space in the 1-up template allows you more freedom to think about details such as visual weight, headings, content and functional elements. Again, you’re trying to communicate how an interface may work, so the details are more important than the fidelity or tidiness of your sketch.

Step 5 – Stick up your sketches

Once you’ve completed your refinement sketch, stick it to your sketchboard, then think about what problem you’re going to tackle next. Return to step 3 and repeat until you’ve sketched everything you needed to when you set out.

Try to keep your sketches in logical groups – use a Post-It note to give your group a heading. Once you’re happy with the position and grouping of your sketches, replace the Post-It headings with inked ones – a big chisel tip Sharpie works well (just make sure the ink doesn’t bleed through the brown paper and onto the wall!).

Step 6 – Evaluate, then evaluate again

Now that you’ve fleshed out your ideas, it’s time to test your assumptions and gather real-time feedback. Ideally, you’ll do this more than once. We tend to have a review session with colleagues first, then we roll up the sketchboard, pop it in a tube and make our way to our client’s offices where we’ll take over the nearest wall (don’t forget the Blu-Tack).

Explain that you’re not trying to sell an idea and that feelings won’t be hurt if the sketches are criticised – indeed, this is the object of the exercise. If you’re feeling particularly brave, start a ‘black-hat’ session where everyone tries their hardest to point out the shortcomings of your sketches. These quick insights will challenge your assumptions, encouraging creative speculation and innovative thinking.

Your clients will appreciate being involved at this stage, and it makes for an enjoyable and productive session – so much better than emailing wireframes back and forth.

During the evaluation sessions, annotate your sketches, use Post-It notes, and amend or create new sketches as required to capture feedback, suggestions and corrections.

Now that your sketchboard is complete, fire up your wireframing or prototyping application of choice and get to work – you’ll find it so much quicker working from your sketches. Your clients will have already developed an understanding of your approach and direction, so you’ll spend less time amending and annotating, or explaining your rationale.

Tools for the job

We use:

- A large roll of heavy paper. You want it to be at least a metre high. We use brown craft paper.

- 6-up and 1-up templates printed on A4 paper. We’ve modified ours slightly by reducing the weight of the outlines and removing the browser chrome. We use these for mobile app design as well as browser-based sites. Environmental tip: To save paper, we print ours on the back of the scrap paper that seems to build up next to our printers.

- Post-It notes. We use loads of these. We only ever use the ‘Super Sticky’ ones as they stay in place when we roll up the sketchboard. We use green ones to identify ideas we like, pink for ideas we hate, and yellow ones to remind us we need to do something.

- Marker pens. We love Sharpies (I think this is probably true of all UX designers). We prefer the black ‘Twin Tip’ pens – one end has a fine tip, the other ultra fine. We use a red marker for bringing attention to something, such as movement or errors. A highlighter pen always comes in useful and a chisel-tipped, grey marker (Warm Grey Letraset Pro Markers are perfect for the job) for adding or removing visual weight.

- Sticky dots for sticking sketches to the sketchboard. Adaptive Path suggest using “Drafting Dots” but we can’t find these for sale anywhere in the UK.

- Blu-Tac (and lots of it) for sticking your sketchboard to the wall.

Note that we don’t use pencils. We tend to go straight to ink to get our ideas down as quickly as possible. If we don’t like something, we scribble it out and keep going. Pencils encourage you to sweat the details, which isn’t the point here.

Conclusion

Perhaps the most compelling reason for using this sketching approach is that it will save you time and money. Sketching is an inexpensive activity, and iteration is quick and relatively painless compared to amending complex wireframes or prototypes. The inherently collaborative nature of the approach will be valued by your clients during thoroughly enjoyable evaluation sessions.

Sketching is hardly a new technique in UX design. I would imagine that the vast majority of UX / UI designers start by putting their thoughts on paper, but how often do clients get to see these sketches? We firmly believe that this collaborative technique can communicate the ideation process much better than wireframes, can save you time and make your clients happier. What’s not to like?

To learn more about the UX services we offer at Box UK, visit the User Experience & Design section of our site.